Research Progress of Spaceflight Rodent Culture Devices and Experimental Techniques

-

摘要: 空间动物实验是人类空间生命科学研究的重要组成部分. 一直以来, 空间动物实验为探索地球生物体在航天环境中的生命现象及活动规律、支持载人航天的可持续性发展做出了重要贡献. 随着航天工程的发展, 航天员在空间驻留的时间越来越长, 为解决人类在空间旅行中的健康问题, 各国先后开展了空间啮齿类动物实验, 研究空间环境给生命体带来的影响, 为人类空间飞行提供重要的生理和医学数据. 本文研究了国外主流的空间啮齿类动物培养装置, 根据各类装置培养动物的存活情况及死亡原因, 提出装置的不足与可改进之处; 深入分析空间啮齿类动物实验发射前、在轨、返回地面阶段的相关实验技术, 为中国空间啮齿类动物培养装置设计及动物实验提供参考.Abstract: Space animal experiments constitute an integral component of human space life science research. Historically, these experiments have made significant contributions to the exploration of the life phenomena and activity patterns of Earth-based organisms within the spaceflight environment, as well as to the sustainable development of manned spaceflight. With the development of aerospace engineering, astronauts stay in space longer and longer. To address the health problems of human spaceflight, rodent spaceflight experiments have been carried out to study the effects of the space environment on living organisms, thereby providing crucial physiological and medical data for human spaceflight. In this work, the spaceflight rodent culture devices developed by foreign countries are investigated. The rodents’ survival status and the causes of death are analyzed, and the shortcomings and improvements of the culture devices are summarized. Then the relevant spaceflight rodent experimental technologies, including before launch, in orbit, and after returning to the ground, are investigated. This work aims to provide references for the design of China’s spaceflight rodent culture devices and rodent experiments.

-

Key words:

- Spaceflight /

- Rodents /

- Culture device /

- Experimental technique

-

表 1 各国啮齿类动物培养装置的对比

Table 1. Comparison of rodent animals in various countries

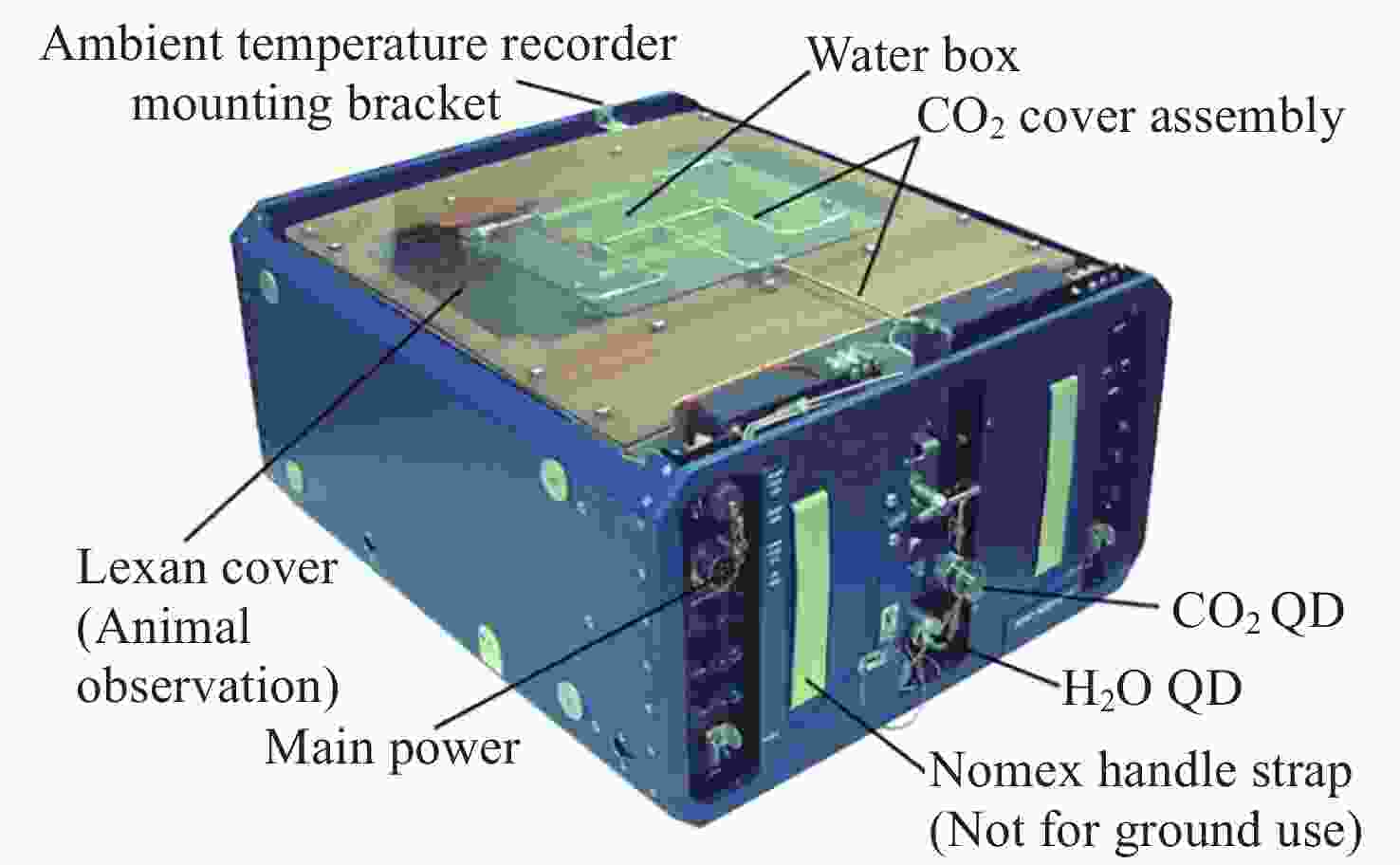

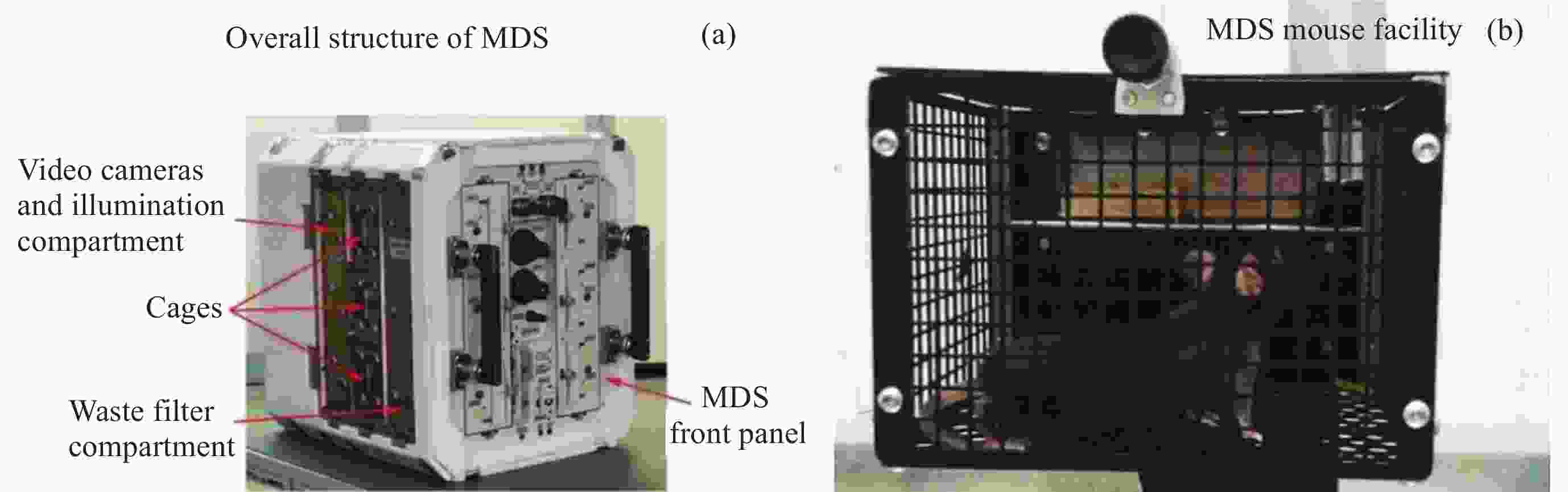

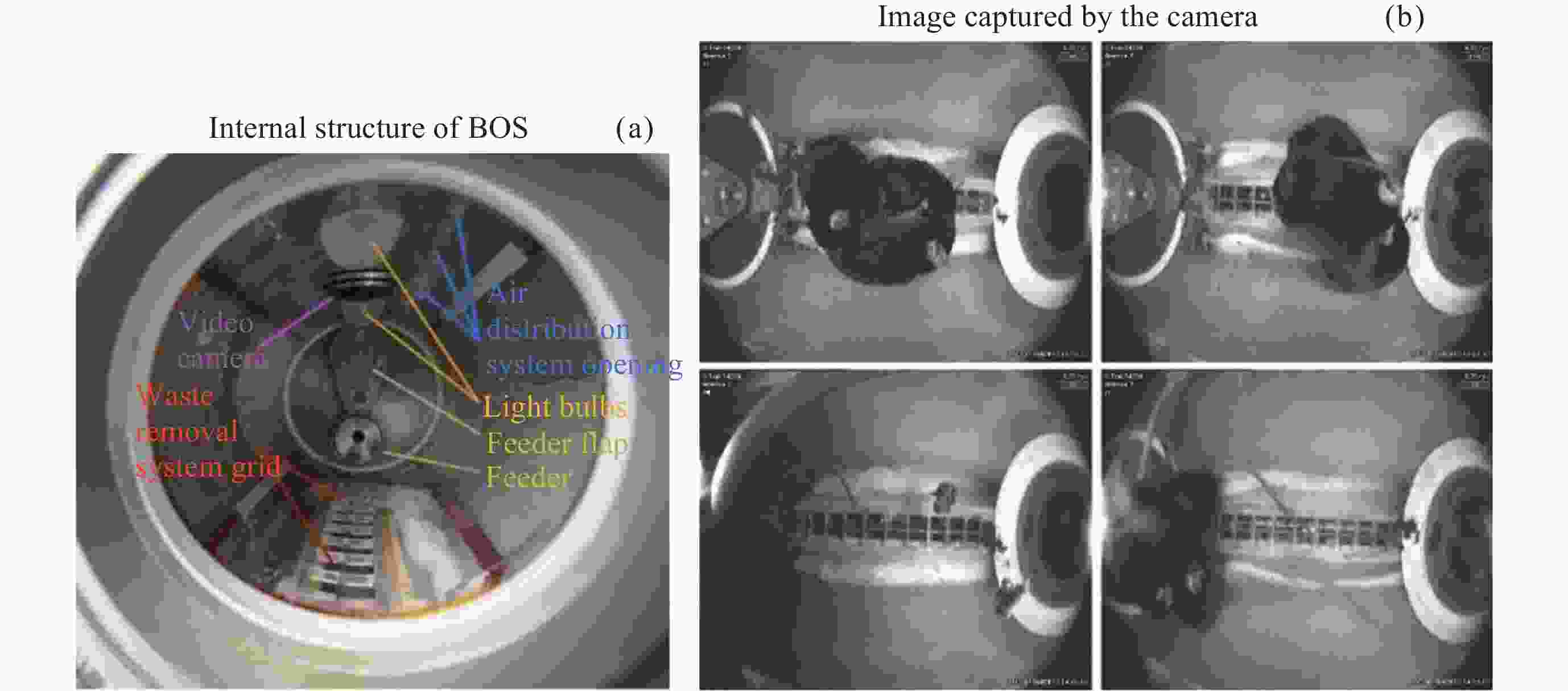

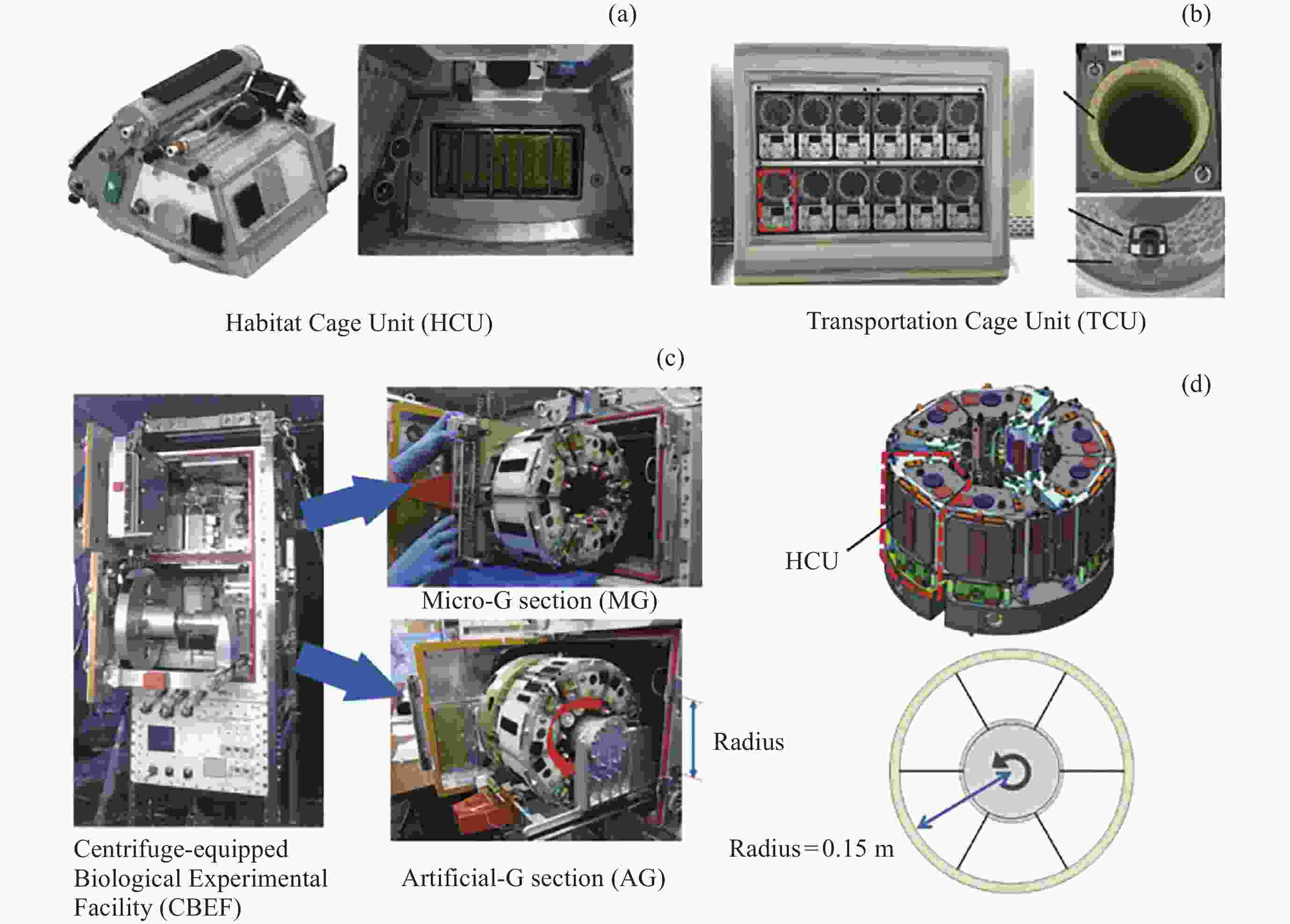

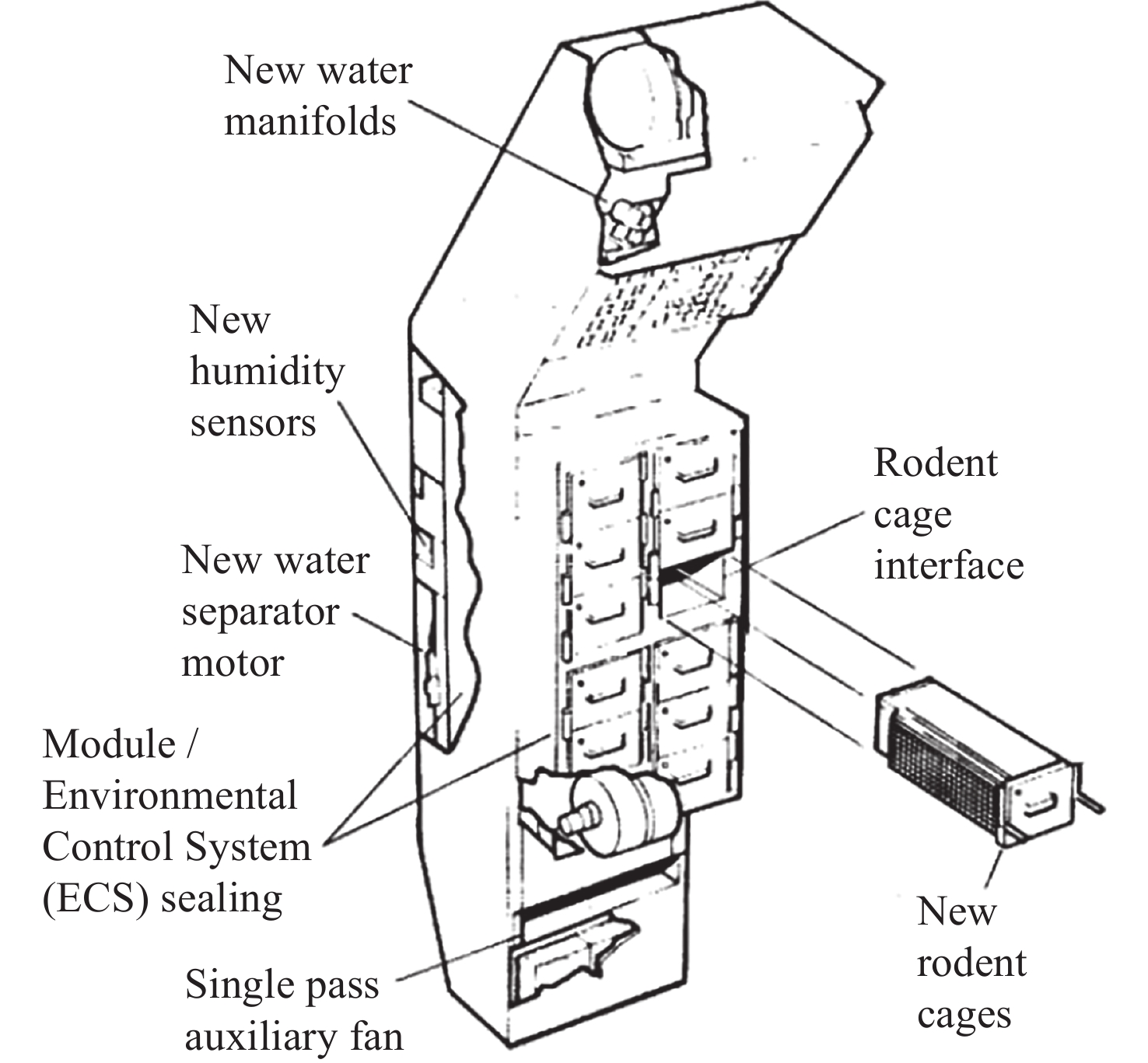

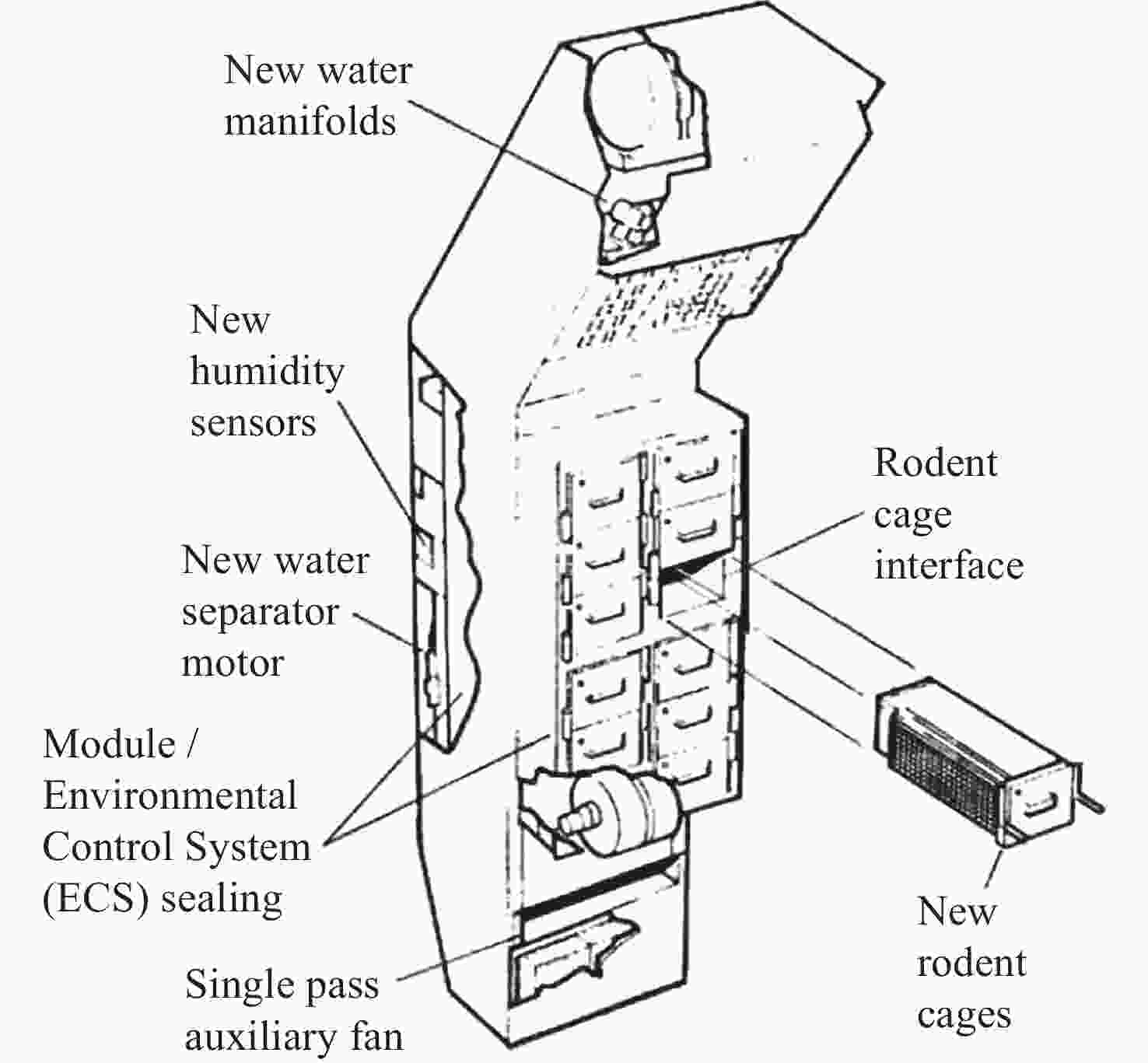

航天局 美国NASA 意大利ASI 俄罗斯IBMP 日本JAXA 硬件设备 RAHF AEM RHHS MDS BOS HCU 应用时间 1985-1998年 1983-2014年 2014年至今 2008年 2013年 2016年 可容纳的小鼠数量 24只小鼠, 每室2只 20只小鼠/6只大鼠, 均分2室 20只小鼠/12只大鼠, 均分2室 6只小鼠, 每室3只 5只小鼠, 每室3只 6只小鼠, 每室1只 生存时长 7~14 d 7~35 d 7~30 d 91 d 30 d 37 d 食物投送 - 每室2个食物盘, 4.57 cm×2.54 cm×4.57 cm食物条 每室2个食物盘,

定制食物每室2条食物条, 每条90 g, 自由采食 每室1个不锈钢喂食器, 3只每日54 g 每室1个食物投送器, 一周一换 饮水 9.5 L总容量 2 L加4 ppm碘的去离子高压灭

菌水加压水箱经Lixit喂水瓶供水 500 mL总容量, 可在轨回收, 自由采饮 - 含0.2 mg·L–1的高压

灭菌自来水墙壁 光滑墙壁 网格墙壁 网格墙壁 网格墙壁 光滑墙壁,

网格过滤光滑墙壁 光强度 - 12 h∶12 h, 14 lux 12 h∶12 h (昼: LED, 夜: 红外) 12 h∶12 h, 0~40 lx, 步长10 lux 12 h∶12 h, (昼: 45 lx, 夜: 5 lux, 红外) 12 h∶12 h (昼: LED, 夜: 红外) 相机监控 无, 通过透明罩观察 每室2台相机,

夜间红外每室2台相机, 夜间红外 每室1个, 实时传输至地面 每室1个,每日2次, 每次8 h,

每秒6帧雨刷器, 1/3英尺

隔行扫描CCD图像

传感器废物处理 O型密封垫片吸附固体颗粒物, 单通道辅助风机除污染物 恒定气流控制装置, 将尿液和排泄物吹入过滤器 除臭过滤器和废水处理器 垃圾过滤器, 含干燥剂控制

湿度底部有废物

清除网格笼壁上的纸片能够清除废弃液体, 其上涂有光催化热喷雾能除臭抗菌 存活比例及死亡原因 视具体项目

而定视具体项目

而定视具体项目

而定3/6, 因升空时发生脊髓病变、食物递送系统故障死亡 16/45, 因食物分配系统故障、群居打斗行为死亡 12/12, 未发生死亡 优势 多层纤维结构吸附固体颗粒物 摄像机视频观察, 红外光夜间

观察由AEM改进, 增加RT、AUU模块, 模块化更方便操作 视频数据实时传输, 使用时间延长 群体饲养雄性小鼠, 观察打斗事件出现的情况; 遥测探头植入, 监测精准 镜头雨刷, 视频数据清晰; 光催化热喷雾能除臭抗菌 不足与

改进无法获取视频数据, 墙壁光滑不利于小鼠移动 没有主动热控制技术, 密闭无法人为外部干预, 需要设置外部接口一边操作和观察 浪费的水和食物被直接收集, 无法区分真正消耗的量与浪费的量 携带数量过少, 食物递送系统故障问题有待改善 平滑墙壁, 小鼠运动受限, 食物分配系统故障, 不可让小鼠直接接触到运动的结构 腐蚀颗粒破坏水喷嘴上的密封引起泄漏, 单独饲养小鼠可能成为其压力来源, 造成生理状况的影响 表 2 实验设备与研究内容

Table 2. Experimental equipment and research content

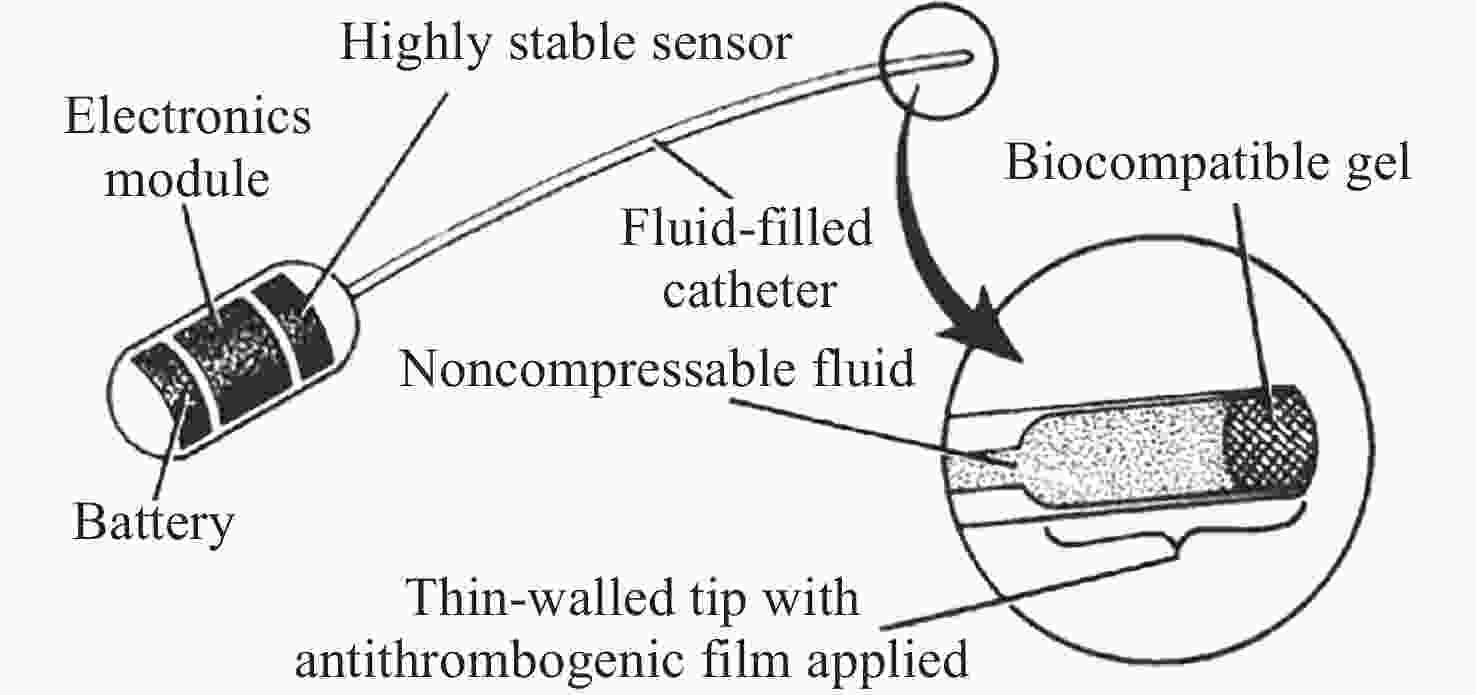

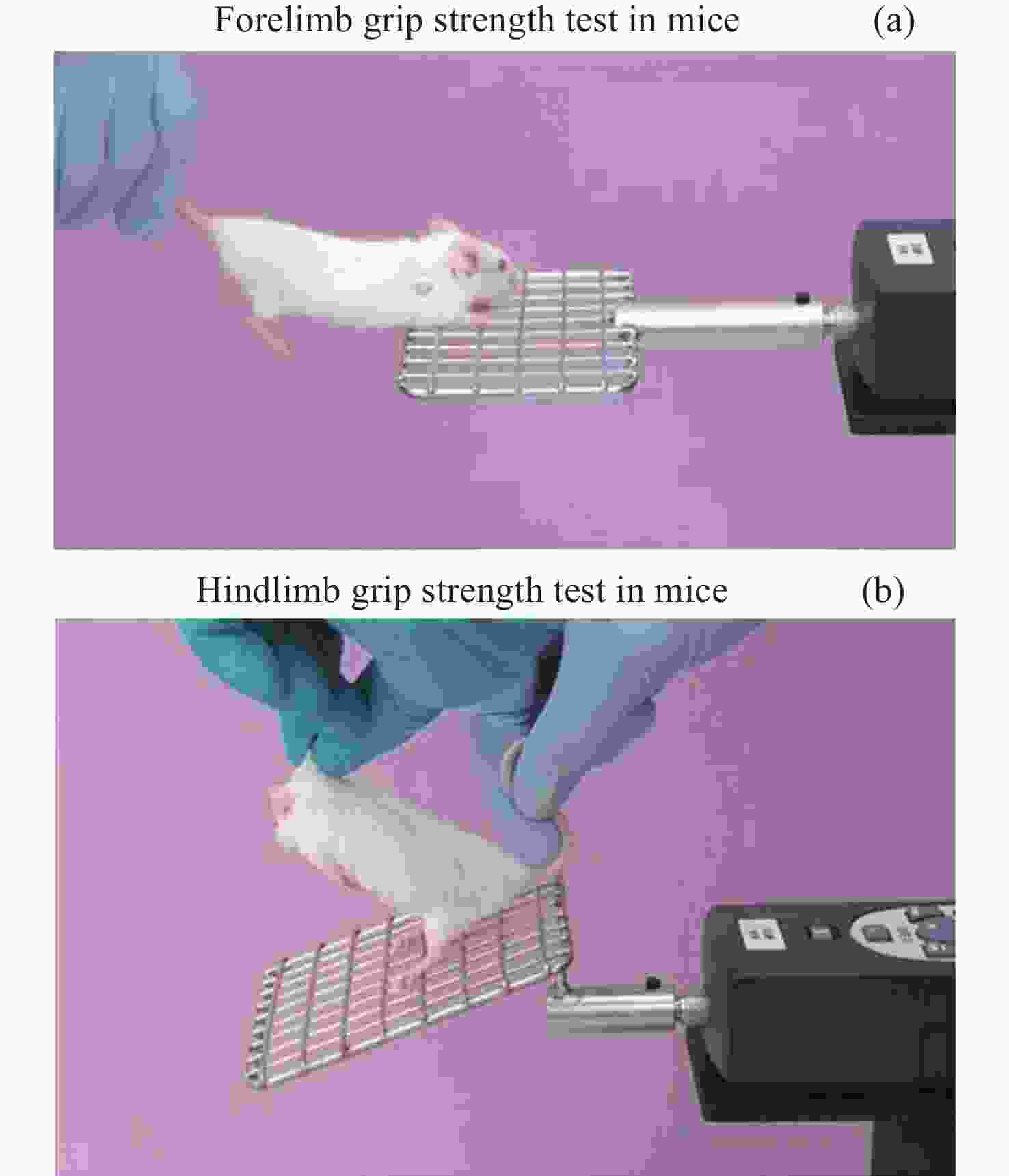

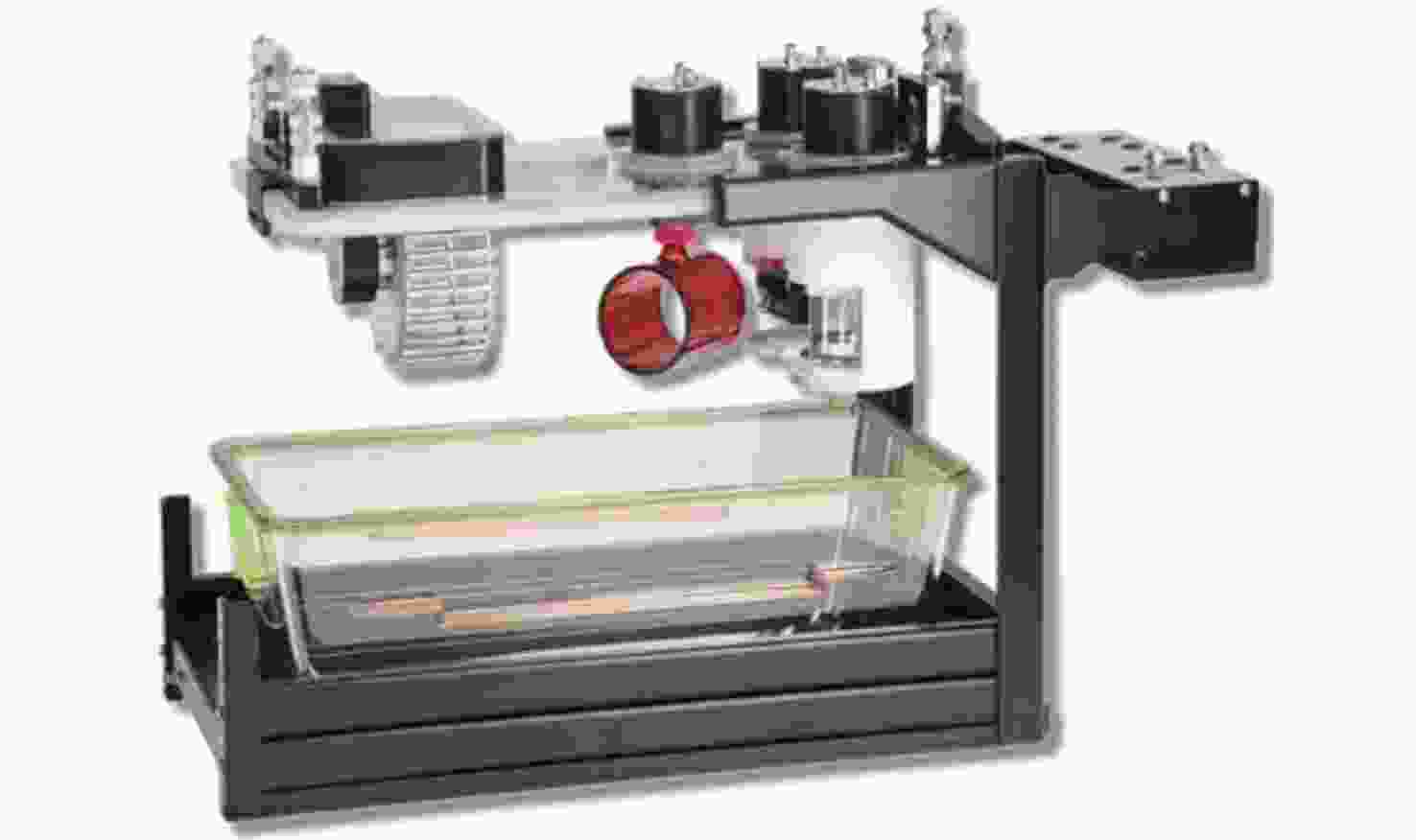

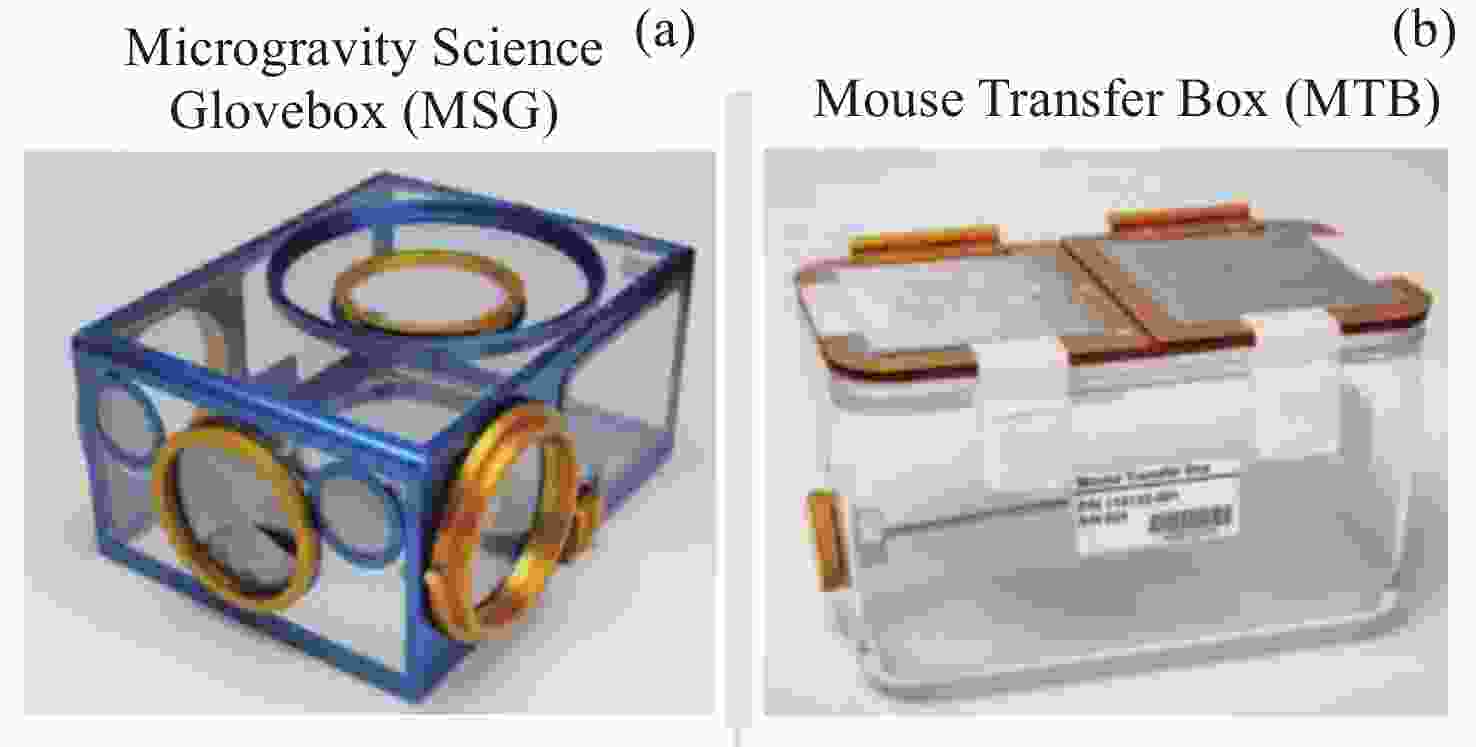

实验设备 参与任务 研究内容 实验环境 植入式遥测设备(PA-C10) Bion-M1 监测血压、心率等 发射前植入, 全过程监测 骨密度计(Bone densitometer) RR-1/3/5 测量骨密度、脂肪比、总质量 在轨检测 握力计 RR-3/6/19 测量四肢肌肉能力 在轨检测 遥测数据收集系统(PhenoMaster) Bion-M1 遥测设备数据收集 在轨检测、地面测试 麻醉恢复系统(Anesthesia recovery system) RR-3 为麻醉和恢复期的动物提供温暖环境 在轨检测、地面测试 在轨解剖系统(微重力手套箱) RR-2/3/5/6 解剖组织器官以便地面分析 在轨操作 步态分析系统(便携式DigiGait系统) RR-9 步态分析, 观察运动行为 地面测试 -

[1] VOELS S A, EPPLER D B. The International Space Station as a platform for space science[J]. Advances in Space Research, 2004, 34(3): 594-599 doi: 10.1016/j.asr.2003.03.027 [2] WNOROWSKI A, SHARMA A, CHEN H D, et al. Effects of spaceflight on human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived cardiomyocyte structure and function[J]. Stem Cell Reports, 2019, 13(6): 960-969 doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2019.10.006 [3] BISSERIER M, BROJAKOWSKA A, SAFFRAN N, et al. Astronauts Plasma-Derived exosomes induced aberrant EZH2-Mediated H3K27me3 epigenetic regulation of the vitamin D receptor[J]. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine, 2022, 9: 855181 doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2022.855181 [4] KRITTANAWONG C, SINGH N K, SCHEURING R A, et al. Human health during space travel: state-of-the-art review[J]. Cells, 2023, 12(1): 40 [5] GEORGE K, CHAPPELL L J, CUCINOTTA F A. Persistence of space radiation induced cytogenetic damage in the blood lymphocytes of astronauts[J]. Mutation Research/Genetic Toxicology and Environmental Mutagenesis, 2010, 701(1): 75-79 doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2010.02.007 [6] BALLARD R W, CONNOLLY J P. U. S. /U. S. S. R. joint research in space biology and medicine on Cosmos biosatellites[J]. The FASEB Journal, 1990, 4(1): 5-9 doi: 10.1096/fasebj.4.1.2403951 [7] SUN G S, TOU J C, YU D, et al. The past, present, and future of National Aeronautics and Space Administration spaceflight diet in support of microgravity rodent experiments[J]. Nutrition, 2014, 30(2): 125-130 doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2013.04.005 [8] CANCEDDA R, LIU Y, RUGGIU A, et al. The Mice Drawer System (MDS) experiment and the space endurance record-breaking mice[J]. PLoS One, 2012, 7(5): e32243 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032243 [9] ANDREEV-ANDRIEVSKIY A, POPOVA A, BOYLE R, et al. Mice in Bion-M 1 space mission: training and selection[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9(8): e104830 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104830 [10] SHIMBO M, KUDO T, HAMADA M, et al. Ground-based assessment of JAXA mouse habitat cage unit by mouse phenotypic studies[J]. Experimental Animals, 2016, 65(2): 175-187 doi: 10.1538/expanim.15-0077 [11] 汤章城. 空间生命科学研究进展[J]. 中国科学院院刊, 1995, 10(2): 128-133TANG Zhangcheng. Advances in space life sciences research[J]. Bulletin of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, 1995, 10(2): 128-133 [12] MA B H, CAO Y J, ZHENG W B, et al. Real-time micrography of mouse preimplantation embryos in an orbit module on SJ-8 satellite[J]. Microgravity Science and Technology, 2008, 20(2): 127-136 doi: 10.1007/s12217-008-9013-8 [13] LEI X H, CAO Y J, MA B H, et al. Development of mouse preimplantation embryos in space[J]. National Science Review, 2020, 7(9): 1437-1446 doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwaa062 [14] 王翔, 王为. 我国天宫空间站研制及建造进展[J]. 科学通报, 2022, 67(34): 4017-4028 doi: 10.1360/TB-2022-0499WANG Xiang, WANG Wei. Development and construction progress of the Tiangong space station in China[J]. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2022, 67(34): 4017-4028 doi: 10.1360/TB-2022-0499 [15] LI J, LIU F W, ZHANG T. Research progress of space mice flight payload[J]. Chinese Journal of Space Science, 2021, 41(3): 445-456 doi: 10.11728/cjss2021.03.445 [16] JENNINGS R T, GARRIOTT O K, BOGOMOLOV V V, et al. The ISS flight of richard garriott: a template for medicine and science investigation on future spaceflight participant missions[J]. Aviation, Space, and Environmental Medicine, 2010, 81(2): 133-135 doi: 10.3357/ASEM.2650.2010 [17] TOTH L A. The influence of the cage environment on rodent physiology and behavior: implications for reproducibility of pre-clinical rodent research[J]. Experimental Neuro logy, 2015, 270: 72-77 doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2015.04.010 [18] GARNER J P. Stereotypies and other abnormal repetitive behaviors: potential impact on validity, reliability, and replicability of scientific outcomes[J]. Ilar Journal, 2005, 46(2): 106-117 doi: 10.1093/ilar.46.2.106 [19] RONCA A E, MOYER E L, TALYANSKY Y, et al. Behavior of mice aboard the International Space Station[J]. Scientific Reports, 2019, 9(1): 4717 doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-40789-y [20] SAVAGE P D JR, JAHNS G C, DALTON B P, et al. The Rodent Research Animal Holding Facility as a Barrier to Environmental Contamination[C]//SAE International Intersociety Conference on Environmental Systems. California: SAE, 1989: 879-886 [21] DALTON P, GOULD M, GIRTEN B, et al. Preventing annoyance from odors in spaceflight: a method for evaluating the sensory impact of rodent housing[J]. Journal Applied Physiology, 2003, 95(5): 2113-2121 doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00399.2003 [22] FAST T, GRINDELAND R, KRAFT L, et al. Rat maintenance in the research animal holding facility during the flight of space lab 3[J]. The Physiologist, 1985, 28(S6): S187-S188 [23] RAINEY K. Rodent Research-1(SpaceX-4)[EB/OL]. [2023-07-23]. https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/station/research/news/rodent_research [24] TOU J, GRINDELAND R, BARRETT J, et al. Evaluation of NASA Foodbars as a standard diet for use in Short-Term rodent space flight studies[J]. Nutrition, 2003, 19(11/12): 947-954 [25] MOYER E L, DUMARS P M, SUN G S, et al. Evaluation of rodent spaceflight in the NASA animal enclosure module for an extended operational period (up to 35 days)[J]. NPJ Microgravity, 2016, 2(1): 16002 doi: 10.1038/npjmgrav.2016.2 [26] BONTING S L. Animal research facility for Space Station Freedom[J]. Advances in Space Research, 1992, 12(1): 253-257 doi: 10.1016/0273-1177(92)90291-5 [27] CHOI S U, RONCA A, LEVESON-GOWER D, et al. Advances in rodent research missions on the International Space Station[C]//Proceedings of the ISS R and D Conference 2016. San Diego: NASA, 2016 [28] TASCHER G, BRIOCHE T, MAES P, et al. Proteome-wide adaptations of mouse skeletal muscles during a full month in space[J]. Journal of Proteome Research, 2017, 16(7): 2623-2638 doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.7b00201 [29] MACAULAY T R, SIAMWALA J H, HARGENS A R, et al. Thirty days of spaceflight does not alter murine calvariae structure despite increased Sost expression[J]. Bone Reports, 2017, 7: 57-62 doi: 10.1016/j.bonr.2017.08.004 [30] LEE S J, LEHAR A, MEIR J U, et al. Targeting myostatin/activin A protects against skeletal muscle and bone loss during spaceflight[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2020, 117(38): 23942-23951 [31] COULOMBE J C, SARAZIN B A, MULLEN Z, et al. Microgravity-induced alterations of mouse bones are compartment- and site-specific and vary with age[J]. Bone, 2021, 151: 116021 doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2021.116021 [32] MAO X W, SANDBERG L B, GRIDLEY D S, et al. Proteomic analysis of mouse brain subjected to spaceflight[J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2019, 20(1): 7 [33] CASERO D, GILL K, SRIDHARAN V, et al. Space-type radiation induces multimodal responses in the mouse gut microbiome and metabolome[J]. Microbiome, 2017, 5(1): 105 doi: 10.1186/s40168-017-0325-z [34] MAO X W, NISHIYAMA N C, BYRUM S D, et al. Spaceflight induces oxidative damage to blood-brain barrier integrity in a mouse model[J]. The FASEB Journal, 2020, 34(11): 15516-15530 doi: 10.1096/fj.202001754R [35] BAINS R S, WELLS S, SILLITO R R, et al. Assessing mouse behaviour throughout the light/dark cycle using automated in-cage analysis tools[J]. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 2018, 300: 37-47 doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2017.04.014 [36] SANDONÀ D, DESAPHY J F, CAMERINO G M, et al. Adaptation of mouse skeletal muscle to long-term microgravity in the MDS mission[J]. PLoS One, 2012, 7(3): e33232 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033232 [37] TAVELLA S, RUGGIU A, GIULIANI A, et al. Bone turnover in wild type and pleiotrophin-transgenic mice housed for three months in the International Space Station (ISS)[J]. PLoS One, 2012, 7(3): e33179 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033179 [38] VAN LOO P L P, VAN ZUTPHEN L F M, BAUMANS V, et al. Male management: coping with aggression problems in male laboratory mice[J]. Laboratory Animals, 2003, 37(4): 300-313 doi: 10.1258/002367703322389870 [39] NASA. Spaceflight-Induced Bone Loss Alters Failure Mode and Reduces Bending Strength in Murine Spinal Segments from Bion-M1[EB/OL]. (2022-02-15)[2023-04-03]. https://osdr.nasa.gov/bio/repo/data/studies/OSD-471 [40] MORITA H, OBATA K, ABE C, et al. Feasibility of a short-arm centrifuge for mouse hypergravity experiments[J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10(7): e0133981 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0133981 [41] SHIBA D, MIZUNO H, YUMOTO A, et al. Development of new experimental platform ‘MARS’—Multiple Artificial-gravity Research System—to elucidate the impacts of micro/partial gravity on mice[J]. Scientific Reports, 2017, 7(1): 10837 doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10998-4 [42] MORITA H, YAMAGUCHI A, SHIBA D, et al. Impact of a simulated gravity load for atmospheric reentry, 10 g for 2 min, on conscious mice[J]. The Journal of Physiological Sciences, 2017, 67(4): 531-537 doi: 10.1007/s12576-017-0526-z [43] ANDREEV-ANDRIEVSKIY A, POPOVA A, LLORET J C, et al. BION-M 1: first continuous blood pressure monitoring in mice during a 30-day spaceflight[J]. Life Sciences in Space Research, 2017, 13: 19-26 doi: 10.1016/j.lssr.2017.03.002 [44] DSI. DSI PhysioTel PA-C10 Pressure Transmitter for Mice[EB/OL]. [2023-09-27]. https://www.datasci.com/products/implantable-telemetry/small-animal-telemetry/pa-c10 [45] NAGARAJA M P, RISIN D. The current state of bone loss research: Data from spaceflight and microgravity simulators[J]. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry, 2013, 114(5): 1001-1008 doi: 10.1002/jcb.24454 [46] MAUPIN K A, CHILDRESS P, BRINKER A, et al. Skeletal adaptations in young male mice after 4 weeks aboard the International Space Station[J]. NPJ Microgra vity, 2019, 5(1): 21 doi: 10.1038/s41526-019-0081-4 [47] MAURISSEN J P J, MARABLE B R, ANDRUS A K, et al. Factors affecting grip strength testing[J]. Neurotoxicology and Teratology, 2003, 25(5): 543-553 doi: 10.1016/S0892-0362(03)00073-4 [48] Columbus Instruments. Grip Strength Meter[EB/OL]. [2023-09-27]. https://www.colinst.com/products/grip-strength-meter [49] TSE. PhenoMaster • TSE Systems - Together through Science and Engineering[EB/OL]. [2023-09-27]. https://www.tse-systems.com/service/phenotype/ [50] CHANIOTAKIS I, SPYRLIADIS A, KATSIMPOULAS M, et al. The mouse and the rat in surgical research. The anesthetic approach[J]. Journal of the Hellenic Veterinary Medi cal Society, 2016, 67(3): 147-162 [51] KEEBLE E. Guide to veterinary care of small rodents[J]. In Practice, 2021, 43(8): 424-437 doi: 10.1002/inpr.124 [52] CHOI S Y, SARAVIA-BUTLER A, SHIRAZI-FARD Y, et al. Validation of a new rodent experimental system to investigate consequences of long duration space habitation[J]. Scientific Reports, 2020, 10(1): 2336 doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-58898-4 [53] JONSCHER K R, ALFONSO-GARCIA A, SUHALIM J L, et al. Spaceflight activates lipotoxic pathways in mouse liver[J]. PLoS One, 2016, 11(4): e0152877 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152877 [54] BEHESHTI A, SHIRAZI-FARD Y, CHOI S, et al. Exploring the effects of spaceflight on mouse physiology using the open access NASA GeneLab platform[J]. Journal of Visualized Experiments, 2019(143): e58447 [55] KWOK A, ROSAS S, BATEMAN T A, et al. Altered rodent gait characteristics after ~35 days in orbit aboard the International Space Station[J]. Life Sciences in Space Research, 2020, 24: 9-17 doi: 10.1016/j.lssr.2019.10.010 -

-

张晶晶 男, 1987年2月出生于湖北省荆州市, 现为中国地质大学(武汉)自动化学院副教授, 博士生导师, 主要研究方向为空间动物生命体征监测与行为智能分析. Email:

张晶晶 男, 1987年2月出生于湖北省荆州市, 现为中国地质大学(武汉)自动化学院副教授, 博士生导师, 主要研究方向为空间动物生命体征监测与行为智能分析. Email:

下载:

下载: